How Mounir Raji honors his Southern Moroccan roots with photography

Mounir Raji, On photography, heritage, and the search for home

What does it mean to long for a place that both exists and doesn’t? A landscape shaped by memory, sun, and scent, a home you visit, but don’t quite live in? Dutch-Moroccan photographer Mounir Raji explores these kinds of questions in his newest exhibition, DREAMLAND – Yallah – Bladi.

Photography as a Language of Belonging

Born in Zaandam (The Netherlands) in 1982 to Moroccan parents, Raji stands within a generation that grew up navigating dual realities. Summers were spent in Morocco, surrounded by extended family, language, landscape, and rhythm. The rest of the year unfolded in the Netherlands: structured, northern, and at times, distant. This duality is not framed in opposition in his work, but as layered texture: a rich field of contrasts, questions, and in-between spaces.

Raji came to photography relatively late, after studying sports economics, but it quickly became his passion. What sets him apart from many of his contemporaries is his use of the photographic image not to capture spectacle, but to hold space. His pictures don’t shout; they speak slowly, allowing viewers to lean in and find their own point of entry. There is a quiet tension in the work of Mounir Raji. A sense of movement and stillness, of being here but also elsewhere. His images often feel like fragments of memory: sun-drenched corners, dusty roads, the pause before someone speaks.

What emerges in his work is a preoccupation with place, not necessarily geography, but emotional geography. Where do we locate ourselves when our cultural references are split? Where does memory end and imagination begin?

Three Narratives, One Ongoing Story

Much of Raji’s recent work can be viewed as a long-form meditation on the concept of Bladi—my country. Not “the country I was born in,” or “the one I live in now,” but the idea of a country: one shaped by memory, longing, and constructed identity.

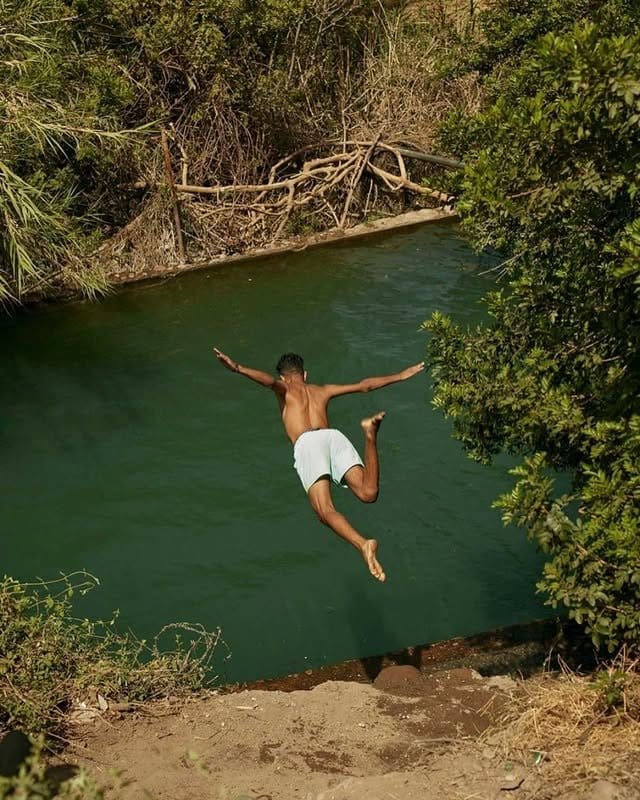

In the series Dreamland, Raji turns his gaze toward childhood summers in Morocco. These are not sentimental snapshots, but carefully composed frames that hold warmth, routine, and stillness. There’s a tenderness to the way he captures cousins sitting in shade, laundry swaying, roads stretching into heat. What’s striking is the intimacy: these images feel lived-in.

In Draa, named after Morocco’s longest river, Raji shifts into a more environmental and documentary mode. Here, the question becomes: what does it mean to be connected to land that is itself changing? The images of the Draa River valley are sparse, contemplative, and almost tactile. The viewer becomes aware of the fragility of place, and the resilience of the people who inhabit it.

Yallah, by contrast, brings us into the dynamic chaos of Marrakesh. It’s the most urban and energetic of the series—men and women on scooters, narrow streets humming with life, a city caught mid-motion. But even here, there’s structure. Raji’s framing is intentional, almost rhythmic, reflecting not just the movement of the city, but the constant momentum of migration and adaptation.

Though his subject is often Moroccan, Raji’s work transcends national identity. It speaks to anyone growing up with more than one cultural background. His images ask: What does it mean to belong? Can you belong to two places at once? And if you can’t, what do you do with the longing?

What makes Raji’s work so compelling, especially to a younger, bicultural audience, is that it doesn’t exoticize. Morocco is not reduced to clichés or spectacle. It’s presented as it’s remembered. A little messy, beautiful, layered. For many, this is the first time they’ve seen their memories represented with this level of care and artistic precision.

In an art world that often privileges the unfamiliar, Raji brings the power of the familiar into focus. And in doing so, he creates space for others like him, but also for those willing to listen, to look, and maybe, to remember.